Here is the overly long story of how I came up with this model. It is not necessary for understanding the model, but it helps explain how this model interacts with an education that focusses on the written word.

When I was writing my Master’s Thesis, I realized that I was struggling to craft a simple thesis statement for my complex research project. That bothered me. I was almost six years into getting an education in History at Carleton University, which has a well-respected history department. I had many quality professors, and I had some excellent teachers in high school. My grade 11 teacher, Ms. Bol, spent two weeks teaching us how to write well-crafted thesis statements, and I used that skill throughout six years of university to do well. But when I had to assemble a large amount of archival information and a literature review into a cohesive, 120-page thesis that was bound together by a simple argument, those skills seemed to temporarily jump ship. With a lot of help from my thesis supervisor (Dr. Norman Hillmer) we were able to craft a strong, simple argument and get through the process of writing a good thesis. Still, the experience left me wondering whether I had missed something in my six years of education.

During the year after I wrote my thesis a few things happened that helped me get my head around what was lacking from my education. I decided to do a second Master’s degree at Carleton (International Affairs, Security and Defence), which meant a third year of being a Teaching Assistant, so I came to job with some previous experience. Second, on the side I tutored a grade 12 student who took a grade 12 philosophy class. The class included lessons on the relationship between premises and arguments, lessons on subjectivity-objectivity and dualism. That grade 12 class helped give me some basic terminology and concepts that I think should have been more prominent in my university education.

Third, I TAed with Dr. Audra Diptee, who really wanted her students to understand the difference between history and the past. The past is objective: it really happened, and it will never change. History is our subjective, and thus fallible, understanding of the past. The field of history constantly grapples with the inherent duality of the past and what we think about it. A good historical paper always addresses that duality, even if it is not explicitly stated in the argument. When I look back at my education, most professors allude to that duality in some way, but each used their own terminology. The range of terms can make it hard for students to really connect the dots between multiple professors across four years of education.

Finally, in a discussion group with my first-years students, I asked if they had any questions about their upcoming paper. One of the better students asked me what a thesis statement was. I could dismiss that and say “you should have learned that in high school” but that would not help anyone. If a good student asks a question it is pretty much always a good question. I realized on the spot that as students progress they are introduced to new concepts and are expected to research and write at a higher level. This should entail that they also need to re-learn how to write thesis statements that incorporate the new things they learn. I ditched the discussion I had planned and I started working with the group to explain what a thesis statement is, but I felt like I was struggling to explain it.

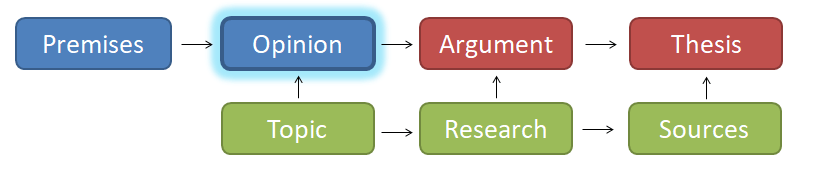

After that discussion group, I got out my whiteboard, and I decided to make a visual graphic thingy to help walk my students through what an argument is in historical writing. History needs more visuals. Once I decided to incorporate elements from the philosophy class and from Dr. Diptee’s “the past and history” lecture it went pretty quickly. There were two basic concepts I wanted my students to really get into their heads. One, there are multiple components that have to work together to have a strong argument. Two, a good historical argument aligns with the historical record, but also engages with other ideas in the field of history. Best of all, by giving the students new terms and concepts I established a common lexicon. That made my job easier by reducing the amount of writing I did when commenting on their papers.

That model did wonders. The papers that were submitted that semester had the greatest bipolarity in the four years I TAed. The students who attended discussion groups wrote good papers. The students who did not attend wrote, to put it diplomatically, papers that had clear room for improvement. Some of them were good writers, but the argumentative approach was lacking. The next semester I TAed a third-year legal studies course, and I almost cried (figuratively) when I saw how many third-year students made the exact same mistakes my first-years made. Did Carleton University fail those students? Or is it their own fault they learned next to nothing?

I didn’t really mean to make a comprehensive model of how to craft a historical argument. I just wanted to help my students get a grasp of what I expected from their 7-page, double-spaced papers. But as my second Master’s progresses I realized that I kept coming back to that model I made because it worked for every paper I wrote. I think it has served me well, so I figured I should share it. So here it is. I also got bored during lockdown and wanted to write, so this is also my entertainment.

There is an alternative explanation to all of this: I could be quite dense, and everyone else in the world immediately grasped what an argument is while it took me six years to get it. I will admit that I am not the best at asking for help, so my social awkwardness has, at times, limited my education. Still, for four years I saw intelligent students struggle to write good papers, so I stand by my claim that we need a greater focus on teaching the production of quality works of writing.